Jethro Tull: A Beginner's Guide To Turnips

If you know just one 1700s agriculturalist who gave his name to a 1970s prog rock band, it's most probably Jethro Tull. But have you read his beloved magnum opus, Horse-hoeing Husbandry? If not, here's just some of what you're missing.

First up: how do you figure out how much horizontal space a turnip needs for its roots? It's not easy, because as the horizontal roots grow further and further from the tap root, they "by their Minuteness, and earthly Tincture, become invisible to the naked Eye." But Jethro figured out an ingenious experimental design:

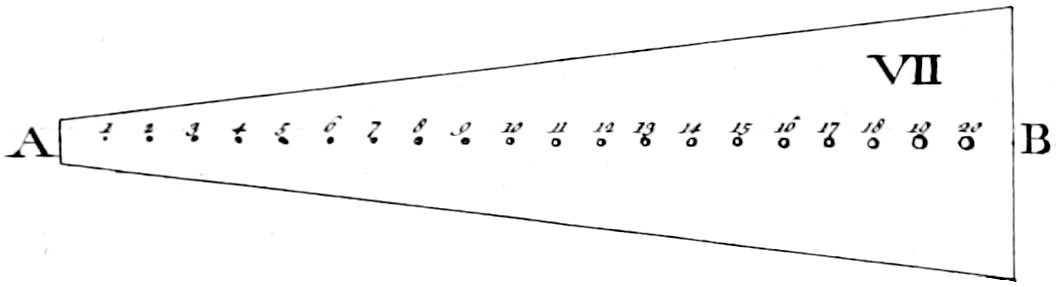

Essentially, you find a piece of hard ground (which turnip roots could not grow in un-hoed), and hoe up a triangular area, "the finer for the Roots to enter, when they are permitted to come thither." Then, plant twenty turnips along the central length. Each turnip has more space to grow its horizontal roots than the previous turnip did, and herein lies your answer: if each turnip is bigger than the previous one, that implies that the roots keep growing to the outer edge of the envelope, in this case 6ft in each direction. If, on the other hand, "Turneps 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 acquire no greater Bulk than the Turnep 15," you can assume that the fifteenth turnip has already maxed out the root space and any additional spacing is unnecessary.

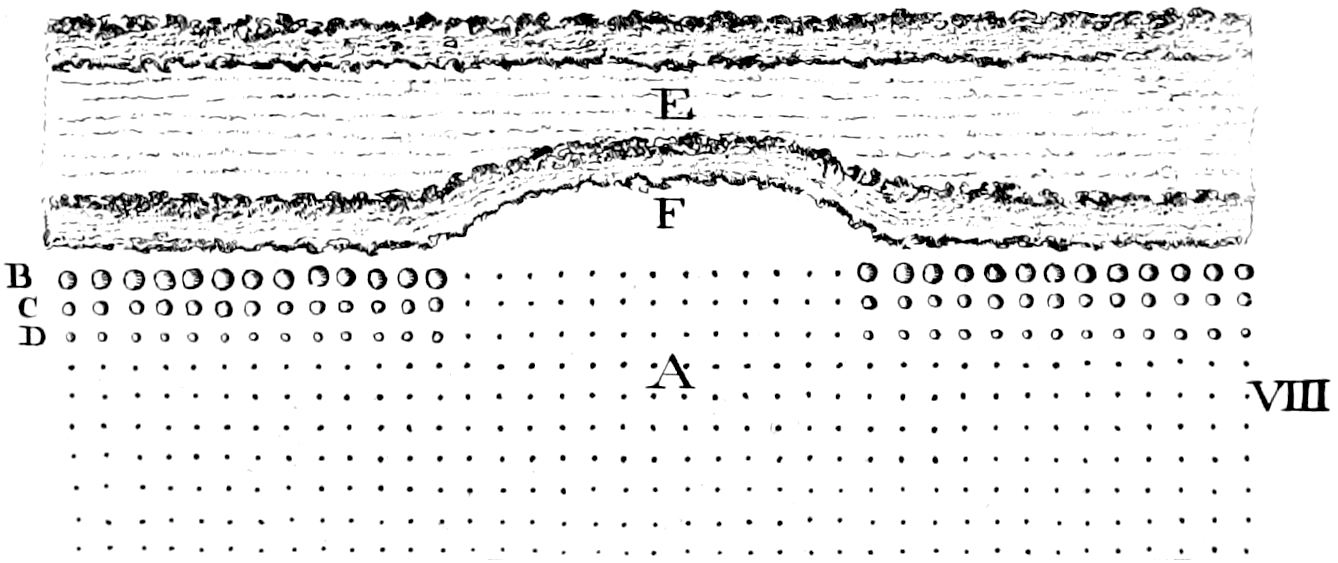

Tull designed this experiment after observing a real-life field with some truly remarkable turnips. Land A (in the diagram below) had not been ho'd, and neither had the land on either side: as a result, most of its turnips were "very poor, small, and yellow."

However, the land in area E had been plow’d and harrow’d, and Tull noticed that the three rows of turnips nearest to it got "a dark flourishing Colour" and grew bigger than all of the rest of the field.

Specifically, Row D – three rows out from the plowed land – "received so much Benefit from it, as to grow twice as big as any of the more distant Rows," and row C grew twice as big again. (Don't get me started on row B, those turnips were ginormous).

Row D is a yard away from Field E, but Tull surmises that the roots heading into E must be going even further (another yard or more), since these few roots are giving "each Turnep as much Increase as all the Roots had done in their own Land."

I know what you're thinking: there's no way the horizontal roots from the turnip are growing out several yards????? But no, you and all your friends are wrong: "One Cause of Peoples not suspecting Roots to extend to the Twentieth Part of the Distance which in reality they do" is because they observe the "Horizontal-Roots, near the Plant, to be pretty taper; and if they did diminish on, in proportion to what they do there, they must soon come to an End. But the Truth is, that after a few Inches, they are not discernibly taper, but pass on to their Ends very nearly of the same Bigness; this may be seen in Roots growing in Water, and in some other, tho’ with much Care and Difficulty." You can't just assume that the Bigness of a root will keep tapering indefinitely, that's silly.

Now, to modern people like ourselves, it may seem obvious that hoeing renders the soil more capable of supplying plants with their nutrients, but in Jethro's day this was not at all known – most people thought that you only needed to ho in order to get rid of weeds. (Be gentle, they didn't know any better). The benefits of ho'ing, and other Principles of Vegetation and Tilage of the New Method, are absolutely bananas: when Jethro tells you the Produce of your Land will be increafed, and the ufual Expence leffened, he is not kidding you.

If you cultivated ten acres of land for twenty years (in 1772's England) in the Old Way, your expected revenue would be £350 0s 0d (~$60k today) and your costs would be £222 18s 4d (~$40k today), leaving you clear £127 1s 8d (about $20k today... over twenty years, mind).

This is absolutely mogged by cultivating the New Way: your produce would be a whopping £560 0s 0d, and even with costs of £297 16s 8d you're left with profits of £262 3s 4d, more than 2x what you got before – "an ample Encouragement to practise a Scheme, whereby so great Advantage will arise from so small a Quantity of Land" if ever I saw one.

And this is all from the conservative estimate of the produce from this method: "Mr. Tull himself, by actual Experiment and Measure, found the Produce of his drilled Wheat-crop amounted to almost Four Quarters on an Acre," which would get you to the completely unprecedented output of more than ONE THOUSAND POUNDS (on ten acres in twenty years), and profits of something like ~£800, more than 6x the profits of the Old Way of doing things.

It is probably obvious by now that I feel about Jethro Tull the way turnips feel about well-aerated soil. And you might be suspicious that I'm too biased in his favour, so let me level with you on a couple of things

1) it does seem that Jethro was not always right: specifically, he thought his ho'ing method completely removed the need for manure (ahem: "High-way Dust alone is a Manure preferable to Dung"), whereas in fact this only works for a limited amount of time (while the humus in the soil, newly exposed to air, provides nutrition to the plants) and eventually you do need regular manure again.

2) I have never farmed anything

On the flip side, there's a couple of things I really want to call out about my boy JT. While I've spent all of 10 minutes trying to find specific calculations of his impact, and another 2 minutes thinking about whether I could perform these calculations myself, and failed: I think there's a decent chance that Jethro Tull is one of those Greatest Positive Impact Humans Who Ever Lived, and if so he's woefully underappreciated for it. Let me put it this way: Norman Borlaug increased wheat yields by 2-3x and is heralded as one of the greatest humanitarians in history. Should(n't) Mr Tull get some proportional celebration?

The second thing I want to call out is just how magical a time (in some ways!) Jethro lived in, where Progress had finally been invented and you could make Observations and do Experiments and figure out how the world works in ways that have massive impact. Of course, the fun part is that we also live at such a time now.